Recently, a team led by Professor Joshua Yang at the University of Southern California and collaborators successfully built a fully functional artificial neuron called 1M1T1R. This artificial neuron can operate like a real brain cell, and it may spur hardware-based learning systems that resemble the human brain, potentially shifting AI toward a form closer to natural intelligence. Media reports suggest this could open the next leap toward AGI and might be a key piece of the AGI puzzle. The related paper was published in Nature Electronics.

Each firing of a 1M1T1R neuron consumes energy at the picojoule level. One picojoule is roughly one thousandth of the energy a mosquito uses in a single wingbeat. The research team’s simulations predict that if more advanced 3-nanometer transistor processes are used and the memristor is further scaled down, its energy consumption could fall to the attojoule level—meaning it would be thousands of times more energy-efficient than a biological neuron.

If billions of such ultra-low-power neurons could be combined to form an electronic brain, then processing current AI tasks that now require massive servers might only consume as much power as a wristwatch battery. This could fundamentally change AI deployment, enabling AI to be embedded into watches, glasses, or even implantable medical devices.

A milestone for neuromorphic computing, helping to realize AGI sooner

Today’s commonly used AI—chatbots, image generators—are narrow AIs: they excel at specific tasks but cannot flexibly apply knowledge from one domain to another. Many hope AGI will be a generalist that can learn autonomously across domains.

How might the 1M1T1R neuron help realize AGI? The key lies in handling spatiotemporal information. Humans live in time and space. When we read a sentence, we need to recognize each character (spatial information) and also understand the sequence they appear in (temporal information). When catching a thrown ball, we need to predict its trajectory and landing point in real time. Processing temporal sequences is a weakness of traditional AI but a strength of the human brain.

The research team built a recurrent spiking neural network using 1M1T1R neurons and used it to tackle a difficult task: recognizing the Heidelberg spike speech digits dataset. This dataset simulates auditory responses in the ear for the digits 0–9 in English and German and is a typical spatiotemporal processing challenge. The network driven by 1M1T1R neurons achieved an accuracy of 91.35%.

The team also found that 1M1T1R neurons possess additional capabilities: their plasticity helps the network propagate learning signals better; their randomness helps the network escape local optima and find more global solutions (like an explorer deliberately taking untraveled paths and finding greater rewards); and their refractory behavior can optimize overall network activation frequencies, enabling adaptation to different tasks.

These results indicate that 1M1T1R neurons do more than simply emulate biological neurons—they are powerful, highly plastic computational units capable of handling the complex, dynamic, real-time computations that future AGI may require.

Their advantage is that each artificial neuron is concentrated within the footprint of a single transistor, whereas previous designs required dozens or even hundreds of transistors to emulate one neuron. Thus, 1M1T1R neurons can reduce chip area by orders of magnitude and substantially lower energy consumption.

U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA among participating institutions

To understand neuromorphic computing, consider this everyday example: when you touch a cup of hot water, your hand reflexively jerks back—sometimes so quickly you haven’t yet felt pain. This action isn’t consciously planned; it’s the result of a highly precise network of brain and nerves automatically responding in milliseconds.

That network comprises hundreds of billions of tiny cells called neurons, which send and receive tiny electrical signals and coordinate everything you do—from breathing and heartbeat to solving a math problem or crying at a movie. Scientists have long asked whether artificial materials that mimic neurons’ behavior could create an electronic brain as efficient and capable as the human brain—hence the field of neuromorphic computing.

To understand the 1M1T1R invention, start with computers and phones we use daily. They follow the von Neumann architecture: CPU and memory are separate. Think of the CPU as a mover and memory as a warehouse. To do a task—say, recognizing a cat in a photo—the mover repeatedly fetches instructions and data from the warehouse, examines them, and returns results. This back-and-forth is energy- and time-consuming and explains why running complex AI heats devices and drains batteries quickly. AI systems like ChatGPT-5 reportedly consume enormous electricity—on the order of the annual electricity usage of over a hundred thousand U.S. households (as reported).

By contrast, the brain weighs about 1.4 kg and consumes power comparable to a dim light bulb, yet achieves cognitive functions that rival supercomputers. This efficiency stems from network structure and operation.

Each neuron in the brain is itself a processing element; neurons are densely interconnected into a massive network. Information is transmitted as electrical spikes in a parallel, asynchronous, event-driven manner—neurons work together without a centralized clock and only activate when signals arrive. To achieve truly efficient and intelligent AI, scientists realize hardware must fundamentally change to mimic this brain-like organization.

Previous attempts used conventional CMOS chips to emulate neurons, but transistors operate very differently from biological neurons. To mimic a single biological neuron’s simple property (for example, accumulating inputs and then firing), tens or even hundreds of transistors were often required to build complex circuits.

This work found a more elegant solution inspired by biological neurons. Biological neurons rely on ions. In the brain, sodium and potassium ions flow across cell membranes, creating voltage changes and generating spikes controlled by ion channels. Is there an electronic device whose behavior can mimic ionic flow? Yes—the diffusive memristor.

A memristor is a resistor with memory. A regular resistor is like a pipe with fixed width; a memristor is like a smart pipe that can change its width: when current flows one way, its resistance decreases and it conducts more easily; when current stops or reverses, it gradually returns to its prior state.

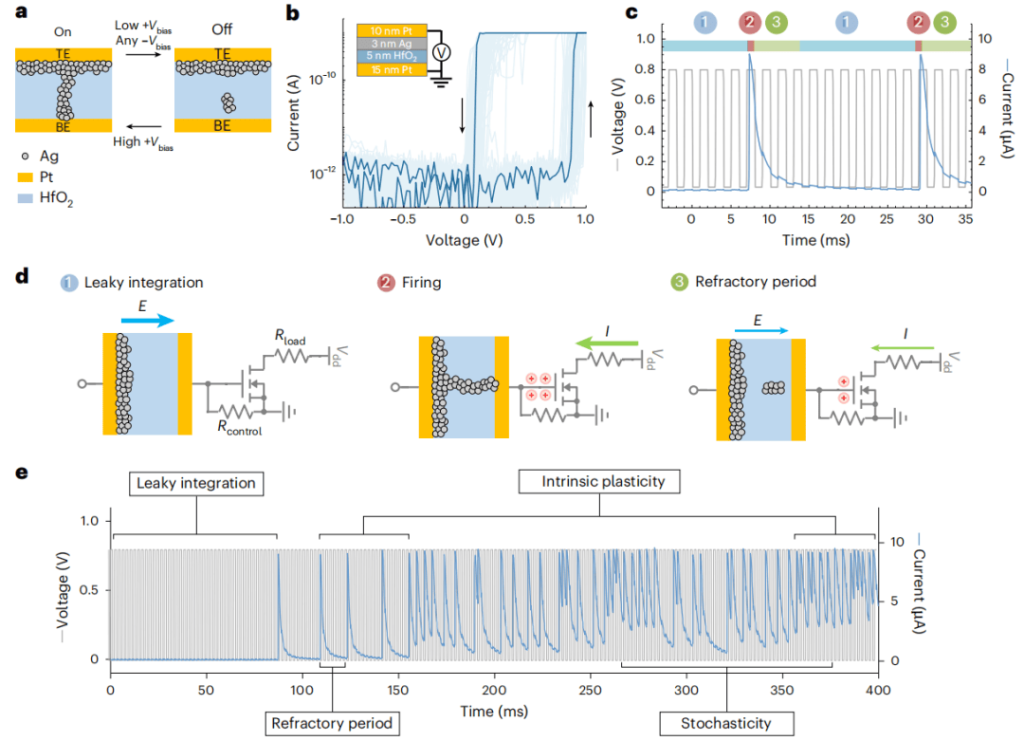

A diffusive memristor is even more intriguing: it contains an active metal like silver. When a voltage is applied, silver ions diffuse and drift, forming a microscopic conductive filament that allows current to pass—analogous to a neuron charging. When the voltage is removed, thermal motion disperses the ions and the filament dissolves, returning the device to a nonconductive state—analogous to neuronal reset.

Based on this principle, the team designed a three-in-one structure called the 1M1T1R neuron, consisting of:

- An asymmetric diffusive memristor at the core, which senses input signals and uses ionic motion to emulate signal accumulation.

- -A transistor that serves as an amplifier and output device. When the memristor suddenly conducts, the transistor’s gate capacitance is rapidly charged, opening the “floodgate” to release a strong output current pulse.

- A resistor that acts like a safety valve and timer, controlling how quickly the gate capacitance discharges and determining how long the neuron must “rest” after firing.

Using nanofabrication, the team vertically stacked the memristor and resistor on top of the transistor. As a result, a complete artificial neuron occupies about the area of a single conventional transistor—an enormous advance in integration density.

The 1M1T1R neuron also demonstrates six key characteristics of biological neurons:

- 1) Leaky integration. Using the water-bucket example: if the bucket has a crack, it takes a long time to fill to the brim; the longer the interval between drops, the more leaks lose water—this is leaky integration. The 1M1T1R neuron accumulates incoming spikes but leaks over time, enabling it to sense temporal patterns.

- 2) Threshold firing. When the bucket finally overflows, water gushes out suddenly. Likewise, when accumulated voltage reaches a critical threshold, the 1M1T1R neuron produces a strong all-or-none electrical pulse.

- 3) Cascaded propagation. One neuron’s output can directly drive the next neuron’s input. The team connected two 1M1T1R neurons and observed that the first neuron’s firing successfully triggered integration and firing in the second—like a row of falling dominoes causing a chain reaction.

- 4) Intrinsic plasticity. Like a piano student getting better with practice, the 1M1T1R neuron shows plasticity. After a firing event, trace amounts of silver ions remain in the filament; when the next signal arrives, these residues make it easier and faster to form a filament again, making the neuron more sensitive.

- 5) Refractoriness. After a strong firing, the 1M1T1R neuron enters a brief refractory period during which it cannot be excited again, no matter the stimulus. The timing of this refractory period is determined by the control resistor and the transistor’s capacitance and can be precisely tuned. This ensures clear rhythm in neural signaling and prevents chaotic activity.

- 6) Stochasticity. Silver ion movement during diffusion is inherently microscopic and random, causing small, unpredictable variations in integration times and firing moments. This randomness helps the system avoid rigid cycles and better adapt to changing environments.

Because of these properties, this neuron type promises far smaller, more efficient chips that process information more like the brain and may pave the way toward AGI. The work involved decades of collaboration among dozens of scientists from USC, the University of Massachusetts, the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory, NASA, and other institutions. Some contributed conceptual design, others patterned devices at the nanoscale, some performed precise electrical measurements, and others developed simulation software—together turning the concept of an electronic neuron into reality.

References:

– Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41928-025-01488-x

– ScienceDaily report: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/11/251105050723.htm

No comment content available at the moment